When to Plant: Frost Dates, Soil Temps, and Timing for Flower Farmers

Picking the perfect varieties for your flower farm is exhilarating—the promise of blooms, the satisfaction of growing your own flowers. But then the seed packets arrive, and suddenly you’re faced with a puzzle:

“Start seeds 4 weeks before the last frost date.”

“Direct sow after the last frost date.”

“Begin indoors 8 weeks before frost.”

And you think: How can I apply the same rules to zinnias and bachelor buttons?

If you’ve grown a home garden before, you probably worked with a single last frost date. But as a professional flower farmer, the game changes. Timing becomes more nuanced. There’s more to consider than just a single frost date.

In this post, we’ll break down the jargon, clarify what those dates mean for different types of flowers, and give you practical tools to create a seed-starting plan tailored to your farm.

Note: This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our farm!

Sorting through seed packets and figuring out when to start—it’s all about turning confusion into confidence!

Hardiness Zone and Its Role in Overwintering

Understanding Hardiness Zones

Hardiness zones are a tool created by the USDA to help growers determine what perennial, biennial, and annual plants can survive winter in their region. They’re based on the average lowest winter temperatures for specific areas, divided into numbered zones. The lower the zone number, the colder the average winter temperature.

While this information is helpful for knowing which crops can overwinter, it’s important to note that hardiness zones don’t dictate when to plant. Instead, they inform whether specific plants can survive in your climate without additional protection.

Navigating Shifting Zones

Hardiness zones aren’t fixed. They’ve been updated several times to reflect changing climate patterns. For example, our area has recently been reclassified as Zone 7, but in practice, it behaves more like Zone 5 or 6, depending on the year. We’ve learned to approach this information cautiously:

When in Doubt: Treat your zone as at least a half-step colder. For example, if you’re Zone 7a, plan as though you’re in Zone 6b to avoid losses during extreme weather.

Adjust Your Planning: Prepare for the worst-case scenario (e.g., harsh winters) while taking advantage of milder years to push planting schedules forward.

Overwintering Crops in Practice

Understanding your zone’s limitations helps you determine what crops can be fall-sown, overwintered, or grown as perennials. For example:

Hardy Perennials and Fall-Sown Crops: Plants like larkspur, nigella, and bells of Ireland thrive when sown in the fall. They establish roots in the cooler months and burst into growth in early spring.

Tender Crops: Some crops, like ranunculus, can technically overwinter in Zone 7. In our Zone’s conditions, this requires additional protection, such as low tunnels or frost cloth, to protect them from extreme temperatures.

By leveraging your hardiness zone and understanding its nuances, you can better plan for seasonal shifts, overwintering success, and crop scheduling.

Looking for top flower crops suited to your hardiness zone? Check out our guide on Top Cut Flowers for Each USDA Hardiness Zone, featured on the Bootstrap Farmer blog!

Rudbeckia chim-chiminee in all its autumnal glory—a reminder that frost dates dictate the perfect timing for blooms like these.

Frost Dates: Timing Your Planting Schedule

Frost dates are one of the most referenced markers on seed packets—and for good reason. They give you a framework for planning when to sow and plant out your crops. However, not all plants respond to frost the same way, and understanding the nuances can make or break your planting schedule.

Let’s break it down:

What Is a Frost?

Frost occurs when temperatures drop low enough to freeze water, causing plant cells to crystallize and potentially damaging or killing the plant. Frosts are classified into two main categories:

Light Frost: Temperatures between 37°F and 32°F. Hardy crops like larkspur, bachelor buttons, and bells of Ireland can usually handle light frosts with little to no damage, especially as seedlings.

Hard Frost (Kill Frost): Temperatures at or below 32°F for an extended time. This can kill most tender plants and significantly damage even hardy ones. Hardy annuals may show frost damage (like drooping or discoloration) but often recover with proper care.

Why Do Frost Dates Matter?

Frost dates are essential for planning when to plant or protect crops, especially in climates with unpredictable weather. They provide guidance for:

Hardy Annuals: These crops, often planted in spring or fall, can tolerate frost and even thrive in cooler conditions. Fall planting allows them to establish strong root systems over winter for a head start in spring.

Examples: Nigella, snapdragons, and larkspur.Tender Annuals: These heat-loving crops are far less forgiving. Planting them too early risks stunted growth, frost damage, or outright crop failure.

Examples: Cosmos, zinnias, and marigolds.

Using Frost Dates Effectively

Frost dates can be divided into two key markers:

Last Frost Date: The average date of the last frost in spring. This is critical for determining when to plant tender annuals that can’t tolerate frost.

First Frost Date: The average date of the first frost in fall. This helps you estimate the end of the growing season for tender crops and plan for fall planting or season extension methods.

Pro Tip: Not sure about your frost dates? Use this frost date calculator to determine the average last and first frost dates for your area. Keep in mind that microclimates within your growing patch may vary.

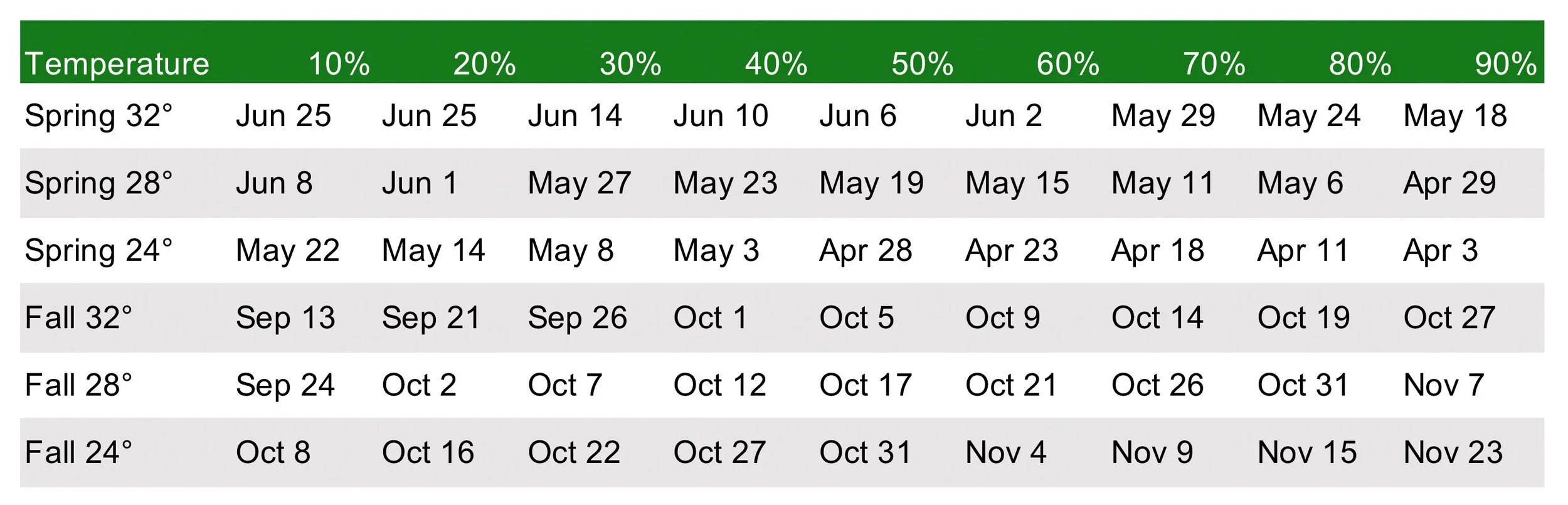

Example of frost-range data for our zip code. While the predicted lows can seem extreme, our experience and note-taking show that planting tender perennials in late April-May often works well. We always prepare protective covers as a precaution!

Using Frost Ranges to Guide Planting Decisions

Frost dates aren’t just about the last or first frost; there’s a critical range between these dates that can help you time your planting more precisely:

Hardy Annuals: These can often be planted earlier in the range—even before the last frost—provided the soil is workable and nighttime temperatures are consistently above freezing.

Ideal soil temperature: 40°F–50°F.Tender Annuals: These heat-loving crops should be planted only after the risk of frost has passed. Nighttime temperatures should consistently stay above 40°F, ideally 50°F+, with soil temperatures reaching at least 60°F, ideally 70°F for optimal root development.

Examples: Sunflowers and strawflowers thrive when planted in the warmer middle of this range.

Additional Tips for Frost Management

Track Your Microclimates: Keep detailed notes about how frost impacts different parts of your field. This data will help refine your planting decisions year after year.

Soil Temperatures as a Clue: While air temperatures may drop below freezing, soil holds heat longer. Use a soil thermometer to identify ideal planting conditions for different crops.

Staggered Planting: Utilize the frost date range to stagger planting schedules. This approach allows for both early-season blooms and summer peak harvests, maximizing your growing potential.

Two Types of Annuals: Hardy and Tender

Understanding the differences between hardy and tender annuals is crucial for planning your seed-starting and planting schedules. These distinctions not only guide when and how to sow seeds but also influence strategies for extending bloom windows, optimizing bed space, and meeting market demands.

Hardy Annuals

Often referred to as “Cool Flowers,” hardy annuals can tolerate light frosts and, in some cases, even hard freezes. These resilient plants thrive in cooler conditions, making them ideal for early planting or fall sowing in many climates. They focus on developing strong root systems during cooler months, resulting in robust plants and abundant blooms in spring.

Examples of Hardy Annuals:

Larkspur

Bachelor Buttons

Stock

Bells of Ireland

Nigella

Temperature Tolerance: Hardy annuals typically withstand temperatures as low as 25–28°F, depending on the variety. Younger plants are often more frost-tolerant than mature ones, making early sowing particularly advantageous.

Pro Tip: Hardy annuals thrive in fall plantings or early spring, producing better results than those sown later in the season. Monitor your local frost patterns and soil temperatures to plan effectively.

Tender Annuals

Tender annuals are the quintessential summer flowers, requiring warm soil and frost-free conditions to thrive. These heat-loving plants are highly sensitive to cold and should only be transplanted after the risk of frost has passed and the soil has reached adequate temperatures.

Examples of Tender Annuals:

Zinnias

Cosmos

Ageratum

Marigolds

Amaranth

Temperature Tolerance: Tender annuals require soil temperatures above 60°F for root growth and are at risk of damage when exposed to temperatures below 40°F. Even a brief light frost can cause significant harm, delaying growth or killing the plants entirely.

Planning Consideration: Unlike hardy annuals, pushing tender crops too early provides no benefits. Wait until conditions are warm and stable to avoid setbacks and ensure strong, healthy plants.

Highlight Successions or Mixed Beds

Integrating hardy and tender crops into your planting schedule offers opportunities to maximize bloom windows, optimize bed space, and cater to market demands.

Temperature-Based Succession Planting: Start the season with frost-tolerant hardy annuals, like stock or larkspur, and transition to tender crops, like cosmos or zinnias, as the soil warms.

Mixed Beds for Continuous Blooms: Pair hardy and tender annuals in the same bed for seamless bloom transitions. Early snapdragons can be replaced by cosmos as they fade, keeping beds productive throughout the season.

Tailoring to Market Needs: Plan successions to align with seasonal demand or event trends. For instance, grow spring hardy blooms like salmon ranunculus to complement summer tender varieties, like cosmos, for consistent color offerings.

Looking to refine your succession planting strategy? Check out our blog on Advanced Succession Planting for Flower Farmers for more insights on extending your bloom window and increasing productivity."

Biennials like campanula thrive when planted with an understanding of frost dates and cold stratification techniques.

Biennials: A Bridge Between Hardy and Tender Annuals

Biennials are a unique category that bridges the gap between hardy and tender annuals in their growing cycle. These plants require two growing seasons to complete their life cycle, making them a bit of a mix between annuals and perennials in how they behave.

In the first season, biennials focus on developing a strong root system and lush foliage. They then go dormant over the winter, requiring a period of cold temperatures (vernalization) to trigger blooming. By the second growing season, they use that stored energy to produce stunning flowers.

Examples of Biennials: Foxglove, Sweet William, and Canterbury Bells.

Why Include Biennials in Your Crop Plan?

Extend Your Spring Offerings: Biennials often bloom earlier than many hardy annuals, filling the gap between overwintered crops and early spring plantings.

Cold-Hardy Dependability: Many biennials can withstand harsh winters with minimal protection, making them a reliable addition to colder growing zones.

Minimal Maintenance: Once established in the fall, they require little intervention beyond ensuring adequate protection from extreme freezes.

Tips for Growing Biennials:

Plant Timing: Sow seeds in midsummer for transplanting in late summer or early fall.

Overwintering: Provide frost cloth or low tunnels for extra protection in particularly harsh winters, especially if you’re growing in zones 5 or 6.

Harvesting Dara flowers—proof that understanding soil temperatures and frost ranges leads to successful crops.

Soil Temperature: A Critical Factor in Seed Starting

Soil temperature is a key but often overlooked element in seed-starting success. Unlike air temperatures, soil retains heat longer, allowing certain crops to thrive even in cooler climates when properly managed. Here’s how to use soil temperature effectively:

Volunteers as Indicators

Nature often provides clues. Watch for volunteer seedlings sprouting in your field—these are natural signals that soil conditions are ideal for sowing or transplanting similar crops. For example, if stock seedlings are germinating under row tunnels, it’s a good indicator to start stock transplants.

Using a Soil Thermometer

When experimenting with a new variety, a soil thermometer is indispensable. Here are key benchmarks:

Hardy Crops: Establish roots in soil temperatures of 50–55°F. Growth may slow in cooler soil but remains viable with larger transplants.

Tender Crops: Require soil temperatures of at least 60°F for active root growth. Warm-season crops like zinnias and cosmos thrive in consistently warm soil (70°F+).

Pro Tip: Take soil temperature readings at the same depth you’ll plant your seeds or transplants—usually 1–2 inches for small seeds and deeper for large-root crops like dahlias.

Timing and Growth

Cooler Periods: Larger transplants with robust root systems fare better in colder soil, allowing plants to establish quickly when warmer temperatures arrive.

Warmer Periods: When soil temperatures stabilize at 60°F or above for three consecutive days, it’s a green light for planting crops like dahlias, even if the air feels cool.

Additional Considerations

Soil drainage affects temperature. Well-draining soils warm faster than clay-heavy or compacted soils. If your soil tends to stay cool longer, plan accordingly or use season extension methods to warm it faster.

Queen Anne’s lace, a hardy annual that benefits from cold stratification, shines as part of nature’s timing.

Cold Stratification: Nature’s Key for Hardy Annuals and Biennials

Cold stratification mimics the natural process seeds undergo in winter to break dormancy. This technique is essential for hardy annuals and biennials that require exposure to cold, moist conditions before germination.

How Cold Stratification Prepares Seeds for Germination

Cold stratification involves exposing seeds to consistently cold temperatures, typically between 32–40°F, for a set period to simulate winter dormancy. This process softens seed coats and activates enzymes necessary for germination.

Crops That Benefit from Cold Stratification

Hardy Annuals: Nigella, larkspur, and bells of Ireland germinate more reliably after a cold period.

Biennials: Sweet William and foxglove seeds often require stratification to break dormancy.

How to Cold Stratify Seeds

Natural Winter Sowing:

Direct sow seeds in late fall or early winter. The natural freeze-thaw cycle softens seed coats and prepares them for spring germination.

Refrigeration Method:

Slightly moisten seeds (not soaking wet).

Place them in a resealable bag with a damp paper towel or vermiculite.

Refrigerate for 4–6 weeks before sowing.

Tips for Success

Check seed packets for specific stratification requirements, as times vary by crop.

Avoid letting seeds dry out during the stratification period.

If direct sowing in late fall, lightly mulch the area to prevent seeds from washing away during winter rains.

Pro Tip: Cold stratification isn’t just for perennials and biennials. Many hardy annuals respond well to this treatment, ensuring stronger germination rates come spring.

Lisianthus in bloom—a reminder of the role photoperiod plays in timing your flower harvests.

Daylight Hours (Photoperiod): The Role of Light in Flower Growth

Daylight hours, or photoperiod, play a significant role in the growth and blooming cycles of many flowers. Understanding this sensitivity can help you maximize your harvest window and ensure optimal blooming conditions.

Understanding Photoperiod Sensitivity

Some flowers are short-day bloomers (spring and fall), while others are long-day bloomers (summer). This information is often included on seed packets under terms like “Harvest Groups” or Roman numerals (I, II, III).

Lisianthus: Grouped by harvest times, with Group I blooming earliest and Group III blooming later, helping you stagger blooms.

Snapdragons: Chantilly varieties thrive under shorter daylight but struggle in long summer days, while Rocket series adapt to both short and long days.

Photoperiod Sensitivity Examples

Sweet Peas: Elegance and Mammoth varieties bloom well in short springs, while Spencer varieties thrive in late spring or cool summers with 12+ hours of daylight.

Heirloom Mums: Choose early bloomers (September) for frost-prone areas or later bloomers (October–November) if using season extension methods, or growing in an area with a later first frost date..

Ranunculus: Short-day bloomers that decline as days lengthen. Shade cloth can extend their viability during longer, warmer days.

Pro Tip: Use tools like daylight hour calculators to predict blooming periods or apply shade cloth to adjust light conditions.

Breadseed poppy seed heads, showcasing the rewards of winter sowing and letting nature guide germination.

Winter Sowing: Letting Nature Guide Germination

Winter sowing is an effective method for hardy annuals like larkspur, bachelor buttons, poppies, and bells of Ireland. Instead of controlled environments, this method relies on nature to dictate germination.

How Winter Sowing Works

Seeds are sown directly into the field during late winter or early spring. They remain dormant until conditions are optimal for germination. This approach simplifies planting schedules and mimics natural cycles.

Best Practices

Sowing Depth: Place seeds at the recommended depth to prevent them from washing away during early spring rains.

Mulching: Apply a light layer of mulch to insulate seeds and retain moisture during temperature fluctuations.

Low tunnels with frost cloth—an essential tool for season extension and frost protection.

Season Extension Methods: Starting Earlier and Growing Longer

Season extension infrastructure like low tunnels, double low tunnels, and unheated hoop houses can make a significant difference in your growing schedule by creating microclimates.

Benefits of Season Extension Methods

Extend planting schedules 2–4 weeks earlier or later than frost dates.

Heat soil temperatures faster, encouraging early crop establishment.

Protect plants from frost, wind, and excess moisture.

Tools and Techniques

Frost Cloth: Use lightweight cloth for micro-tunnels to stabilize soil temperatures and shield plants from frost.

Row Tunnels: Pair tunnels with drip irrigation to ensure consistent moisture while protecting plants.

Pro Tip: Combine frost dates with season extension methods to create a tailored planting and seed-starting schedule. For more tips, visit our blog on Season Extension Strategies for Flower Farmers.

Anemones and sweet peas thriving side by side, illustrating the balance between frost tolerance and season extension.

Freeze-Thaw Effects: A Hidden Challenge for Overwintered Crops

One of the biggest challenges in cooler climates is the freeze-thaw cycle, where temperatures fluctuate between freezing at night and thawing during the day. This cycle can wreak havoc on crops, especially those overwintered with minimal protection.

How It Affects Crops

Soil Disruption: The expansion and contraction of soil can heave plants out of the ground, exposing roots to air and causing desiccation.

Root Damage: Even cold-hardy crops like ranunculus are vulnerable if their root systems are repeatedly disturbed by soil movement.

Moisture Stress: Ice formation and thawing can create waterlogging, suffocating roots and increasing the risk of rot.

Mitigation Strategies

Mulch: Apply a thick layer of mulch or straw around overwintering crops to insulate the soil and reduce temperature fluctuations.

Frost Cloth and Low Tunnels: Cover beds with lightweight frost cloth or use low tunnels to stabilize soil temperatures and protect plants from extreme shifts.

Planting Larger Root Systems: When overwintering hardy crops, opt for transplants with established root systems to better withstand soil movement.

Pro Tip: When dealing with freeze-thaw cycles, monitor soil conditions closely. Avoid working wet soil, as compaction can exacerbate heaving.

Tetra-double feverfew—successfully grown with the help of careful note-taking and understanding frost and planting timelines.

Applying the Information

Your frost dates, microclimate observations, and tools like soil thermometers and daylight calculators provide the foundation for a successful growing schedule. Remember:

Hardiness zones determine overwintering potential.

Frost dates guide planting decisions for hardy and tender crops.

Soil temperatures and photoperiod sensitivity optimize seed starting and bloom timing.

With detailed records and the right tools, you’ll refine your approach each year and enjoy healthier, more productive crops.

We are looking forward to sharing more blooms with you soon.

Jessica & Graham